- Home

- Jeff Diamant

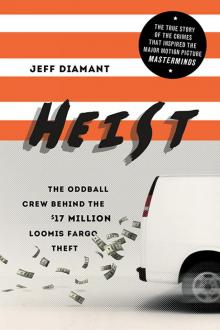

Heist Page 8

Heist Read online

Page 8

Though she could’ve hidden her involvement better if she wanted, it had been a stretch for Kelly to think she could keep her husband out of the loop in the first place. She finally told him the truth. He had figured as much, he said. Getting mixed up in this would change his life, and he was smart enough to be worried. Unfortunately, at the moment he was in no position to protest much, because Steve and Michele were his ride back to North Carolina.

Tercel to BMW

Loomis Fargo wanted to make somebody else rich—but this time on the company’s own terms. Soon after the heist, Loomis posted a $500,000 reward for information leading to an arrest or conviction in the case, hoping it might produce a real lead in an investigation threatening to go cold fast. In mid-November, the company still held out hope a tip would produce results about David Ghantt’s location.

Loomis, Fargo & Co. was formed in 1996 when Borg-Warner Security Corporation of Chicago, which owned a company called Wells Fargo Armored Services, merged with Wingate Partners of Dallas, which owned Loomis Armored. The new company, which employed 8,500 people, was owned 51 percent by Loomis shareholders and 49 percent by Borg-Warner Security.

The roots of the armored-transport industry date to the mid-nineteenth century and the California gold rush, when successful prospecting companies relied on horse-drawn carriages to safely transport gold. With the rise of railroads later in the century, trains became the favored way to move cash.

According to Heists: Swindlers, Stickups, and Robberies that Shocked the World by Sean P. Steele, modern practices date to the 1920s, when Brink’s Express—now called Brink’s Inc. and the largest armored-transport company in the United States, but back then a freight company—leased a school bus fortified with steel to Chicago companies transporting large amounts of cash. The idea caught on. Armored vehicles were faster and safer than the armed couriers then working in cities, and they were less vulnerable to robberies than trains.

Demand for armored cars increased dramatically after World War II, when the mass suburbanization of the United States led to more openings of banks outside of cities. Decades later, the large armored-car companies were transporting hundreds of millions of dollars each day. Still, they operated with slim profit margins because banks—which comprise much of their business—did not pay the companies any more than they had to. That was partially because bank officials cared little about who transported their cash as long as the movement was insured, which it was, by the armored-car companies themselves.

Loomis Fargo’s announcement about its reward, combined with the coverage on America’s Most Wanted (the network had replayed the Ghantt segment to make up for the ball-game snafu), had led to a barrage of tips, but none panned out. Many of the leads seemed inspired by non-heist-related pettiness. He just bought a BMW, and his last car was a Tercel! The agents had to check them out, but it was so easy to relay minor suspicions to the FBI that the bureau seemed overwhelmed with meaningless tips.

Then came a needle in the haystack. In the last days of October, a legal assistant from Jeff Guller’s office called and told the hot line operator that a man named Steve Chambers had an extremely large amount of cash stashed in her employer’s office and that it seemed suspicious, given the heist. The America’s Most Wanted operator replied that they were not looking for anybody named Steve Chambers. That was the end of it.

Meanwhile, the FBI had received permission from a federal judge to monitor the telephone lines of Kelly Campbell, Tammy Ghantt, and Nancy Ghantt, David’s sister. The phone-monitoring devices, called “pen registers,” revealed the length of calls in progress as well as who called whom. Pen registers don’t involve recording phone calls; that’s the province of wiretaps, considered much larger infringements on citizens’ privacy and thus harder for the FBI to gain permission to use. To have a judge allow a wiretap in this case, the FBI would need much more evidence and demonstrate that agents already had exhausted less intrusive approaches.

The judge’s order gave the FBI permission to place pen registers on the phone numbers for two months. Meanwhile, the U.S. attorney’s office subpoenaed toll records, which show records of past calls—who made them and how long they lasted.

The toll records indicated that Kelly Campbell had lied, that the numbers registered to Campbell and David Ghantt had telephone contact on October 3 and October 4, the day of the heist. Campbell had told the agents she hadn’t talked to Ghantt for at least two or three weeks before the theft. They also began to suspect she’d been lying when she told them she and David smoked marijuana together. Loomis officials had since told the FBI that Ghantt passed his company drug tests.

Halloween came and went without any breaks in the case. Then, in the second week of November, the publicity began bearing fruit. An anonymous caller told the FBI she knew a woman named Michele Chambers who had just moved into an expensive house she shouldn’t have been able to afford.

A few days later, on November 12, the FBI received another intriguing call about Chambers and her husband, Steve. The anonymous caller said that the couple had been living in a mobile home in Lincoln County until two weeks earlier, and that Steve and Michele had just bought a large, expensive house at the exclusive Cramer Mountain gated community in Gaston County.

The caller had no proof that they were involved in the heist, but the whole thing seemed suspicious because neither Steve nor Michele held a steady job. Steve was just a small-time crook who had been involved in holding stolen property, the caller said. When the caller had asked Michele how they could buy such a big house, Michele had beaten around the bush, saying that the seller and an attorney were taking care of things.

None of which proved, of course, that Steve Chambers was involved in the heist. His newfound cash could have been drug money or gambling winnings, or who knows what. But the feds planned to keep an eye on him. The supervisors assigned John Wydra to check out the Chamberses and their house purchase, figuring Wydra’s experience investigating money laundering and financial transactions would be helpful.

Wydra drove from Charlotte to Gastonia, where the Gaston County Courthouse sat downtown across the street from a barbershop and a furniture store, to check the deed for the house transaction. As he walked up the steps of the courthouse, Wydra was unaware that Steve and Michele Chambers were starting up their furniture business a few hundred feet away.

Inside the courthouse, records showed that Steve and Michele’s new house cost $635,000 and that they had paid most of it down, needing a loan for less than $200,000 of the purchase price. Wydra also researched their criminal records and learned of Steve’s guilty pleas for obtaining property by false pretenses. The records on his case included a series of aliases he had used for the scams, and Wydra punched these into the FBI’s database. They were names that wouldn’t ordinarily turn heads—Robert Dean Wilson, Steven Jeffcoat. The case record showed Chambers was a scam artist and small-time crook, not someone capable or even interested in a crime of this magnitude.

But on November 18, the FBI received another confidential call that stood out. It was about a man named Eric Payne. According to the caller, Payne had gone on vacation for two weeks, starting the day after the heist, and was now spending more money than he should’ve been able to afford on his salary. He had just bought a new Chevy Tahoe and had explained his new wealth as an inheritance. Plus, the informant said, he worked at Reynolds & Reynolds, located less than a mile from the wooded area where the Loomis van had been found two days after the theft.

Agent Dick Womble dealt with this call. First, he checked records to see if any of Payne’s relatives had recently died. None had, so the excuse about the inheritance seemed sketchy. Womble also drove to Reynolds & Reynolds and spoke discreetly with officials there. He learned that Payne had attended East Gaston High School and that Steve Chambers had briefly worked at Reynolds & Reynolds, years earlier when it was under different ownership.

The FBI now knew tha

t Steve Chambers and Eric Payne, independently, were spending a lot of money. But the agents had no solid way to tie them together—besides knowing both had worked at Reynolds & Reynolds and attended East Gaston High School—or to tie them to David Ghantt or Kelly Campbell. The agents didn’t even know if Chambers and Payne were spending Loomis money. The proximity of Payne’s workplace to the van seemed a possible indication of something, but it could’ve been a coincidence.

A link between the suspects, if only a minor one, came when agents obtained permission to include Steve Chambers’s phone numbers in the pen registers and toll records. They noticed continued phone contact between Payne and Chambers, and also that Jeff Guller, the attorney who had called them the week after the heist about Kelly Campbell’s refusal to take a polygraph, had had phone contact with Chambers the next day. Maybe Chambers and Campbell knew each other, though that was uncertain. The connection was nothing to seek an arrest warrant on, but for the first time the FBI had a way to link Steve Chambers to Kelly Campbell.

The agents cross-checked every new name with the monthly reports of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, a bureau of the U.S. Treasury Department that coordinates information in suspicious activity reports filed by banks nationwide. The FBI hoped Kelly Campbell, Steve Chambers, or Eric Payne would show up on its compiled list, but since the reports often took two or three months to weave through official channels to the FBI, that hadn’t yet happened. A report taken in October usually wouldn’t reach agents until mid-December or later.

Connecting Steve Chambers to Kelly Campbell, however tenuous the link, seemed like an important step. After all, Campbell had been on the phone with Ghantt the day of the crime and had lied about it to the FBI. And despite all the informants and interviews, the FBI still had no clue if David Ghantt was dead or alive. And if he was alive, the agents had no idea where he might be. Idaho? Mexico? Venezuela? He could’ve been anywhere, even in Charlotte.

Anxious for a new approach around Thanksgiving, the FBI engaged the inexact science of behavior profiling. Dick Womble and Mark Rozzi drove from Charlotte to Stafford, Virginia, to the FBI’s National Center for Analysis of Violent Crimes. The behavioral analysis unit there focused on finding serial killers, rapists, and kidnappers, stockpiling databases and tips from crimes across the country that helped it devise theories about where fugitives with similar backgrounds might have gone. David Ghantt didn’t fit the bill of what the unit normally studied, but Womble and Rozzi figured the experts’ eyes wouldn’t hurt. They had already discussed the case with the unit’s experts over the phone, but they wanted to talk with them in person.

Womble and Rozzi told the people there everything they’d learned about Ghantt and his family. They mentioned that his relatives and friends said he liked reading about counterintelligence and the FBI. They mentioned his coworkers said he’d complained about his marriage and suspected an affair between him and Kelly Campbell. They disclosed that the coworkers said Ghantt had frequently criticized Philip Johnson—the man who had pulled off the bigger heist in Jacksonville—and would say things like, “Where that guy screwed up was, he stuck around. He should’ve cut all ties.”

The unit’s experts processed the information. Ghantt’s physical build suggested he probably couldn’t have moved all the money by himself and that he probably needed help with the crime, the experts told Rozzi and Womble. Many of Ghantt’s favorite novels had plots with spies fleeing to Central and South America, so perhaps he was somewhere there, trying to live the fascinating life of one of the characters and avoiding Philip Johnson’s error. And yes, Ghantt’s marital history gave reason to suspect that another woman was involved, the experts said.

The conclusions seemed simple to have come from behavior-profiling experts, and they seemed similar to what agents had already surmised. But Rozzi and Womble were glad that the bureau had drawn reasonable preliminary conclusions and seemed on the right track.

• • •

Meanwhile, Kelly Campbell remained the target of periodic physical surveillance, which revealed in mid-December that she was driving a new Toyota minivan. Agents jotted down the license plate number, which allowed them to start tracking the purchase and registration information.

Womble and Rozzi, back in Charlotte from Virginia, tried their luck again on Campbell, calling her on December 29 to set up another meeting nearly three months after their previous one. They wanted to talk with her about Ghantt and ask her again to sit for a lie-detector test. Campbell was busy that morning but was available to meet in the afternoon at the Gaston Mall.

Once there, they sat down over coffee, making small talk about Kelly’s son, who was recovering from appendicitis. Then they got down to business.

“We’re still trying to locate David Ghantt,” Womble told her.

Kelly stayed true to her prior story, saying she had no idea where he was. During their fifteen minutes together at the mall, Kelly’s cell phone and pager were ringing and buzzing almost constantly, but she didn’t respond to them. Womble and Rozzi managed to hide their wonder at this. They also concealed their own knowledge, developed through the toll records, that she had previously lied concerning her contact with Ghantt before the heist.

“We think there’s more to this than you’re telling us,” Womble said. “Would you take a polygraph for us?”

She told them to call her attorney, Jeff Guller, with their questions. They shook hands with her and she left. Neither agent believed she would ever agree to take the polygraph.

• • •

On December 28, a man placed a call to the FBI with information about Steve Chambers. He said he had never met him but that he knew a guy named Mike Staley, who had sold Chambers his furniture store in Gastonia. The caller had talked with Staley, who told him he had been inside Steve’s new house and had seen a bag so heavy with twenty-dollar bills that Steve had trouble lifting it. The caller suspected Chambers was in on the heist. For the FBI, this was another tip that something was awry with Chambers.

By the end of 1997, nearly three full months into the investigation, the FBI had used phone and car registration records to connect three important suspects. Campbell had been shown by phone records to have lied about her contact with David Ghantt on the day of the crime, and her lawyer had telephone contact with Steve Chambers the day after having called the FBI on her behalf.

At the same time, agents had no reliable leads on David Ghantt’s location and no firm sense of whether he was alive or dead.

Dead Man in Mexico?

The international fugitive could last only so long on $25,000. His heady October days of lobster, parasailing, and fancy hotels quickly ate away at David Ghantt’s first heist installment. In the first week of November, he realized he needed more cash, and he wanted it fast. To his extreme displeasure, he had yet to receive his one-third share of the loot.

The man who pulled off a $17 million heist was thus reduced to eating homemade grilled cheese sandwiches and pasta, saving his money in case the next sum failed to arrive in a timely fashion. He was renting an apartment with a kitchen for about $800 a month, decorating the walls with Pittsburgh Steelers paraphernalia near Cancun’s beach off Kukulkan Boulevard.

He wasn’t alone. He had met a woman named Lindsey, who was twenty-four years old and Canadian, as far as David knew. He’d met her at Christine, his favorite hangout. As far as Lindsey knew, David was a small-time drug dealer from the States, and his name was not David, it was Mike McKinney. His shadiness did not bother her. Every so often, she somehow popped up with a wad of cash herself.

The Cancun couple drank at local clubs and went scuba diving; he had purchased $3,000 worth of diving equipment and a navigational device for $900 more. She moved in with him after getting kicked out of her own place in the middle of November. They hosted parties attended by her friends, who were Ecstasy dealers, and while David never indulged in their wares, he enjoyed their com

pany.

Lindsey had a friend who worked for a car-rental company, and one day David and his girlfriend rented a Volkswagen Beetle to go driving outside Cancun, blowing the speed limit and then some. It was hardly his most serious transgression of the year. Still, a local police officer’s siren blared behind them.

As they were stopped on the side of the road, David was confident his Michael McKinney ID would stand up to scrutiny. Nobody had given him trouble over it yet. He rolled down his window as the officer walked up to the car.

“It’s very hot today, sir,” the officer said. “I’d like a drink.”

David had heard about the police in Cancun and knew exactly what to do. Without a word, he placed sixty dollars in the ticket book the officer was holding out to him.

“Have a nice day,” the officer said. He drove away and left them to enjoy themselves, never even checking the ID.

• • •

The Cancun fling with Lindsey was only so fulfilling. From a pay phone, David called Kelly Campbell on Tuesdays using a calling card and demanded the first installment of the rest of his money. He wanted fifty grand as soon as possible, he told her.

Kelly relayed his words to Steve, who had her tell David they would send a man answering to Bruno to Cancun with cash for him. She relayed this to David, who suggested they meet at the Rainforest Café in Cancun.

Back in North Carolina, the hit man’s trip to Mexico almost ended before it began. The real Mike McKinney, a.k.a. Bruno, was not an especially good smuggler. In the men’s bathroom at Charlotte Douglas International Airport, he bundled the $10,000 given to him by Steve inside the waist of his jeans and prepared to walk through the metal detector. As he exited the bathroom, though, the money began falling down his pants! He scurried back inside, his heart stopping as he envisioned airport security swarming around him.

Heist

Heist